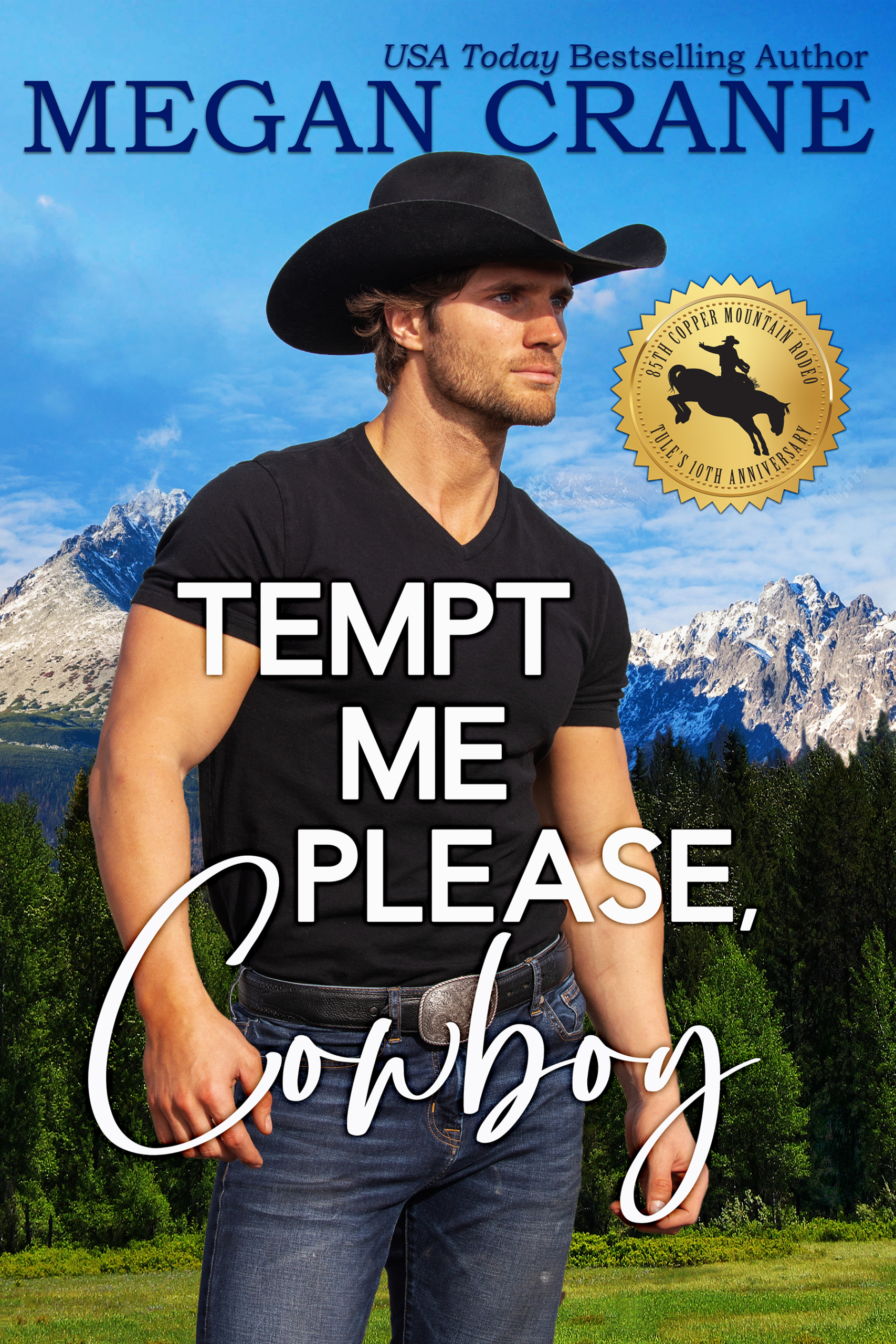

Tempt Me Please, Cowboy

Part of the

Greys of Montana Series

Part of the

Montana Millionaires Series

HEAT

LEVEL:

Satisfyingly Spicy

Welcome back to Marietta, Montana…

This brand new Copper Mountain Rodeo book comes out ten years after Tempt Me, Cowboy kicked off the 75th Copper Mountain Rodeo series—and was the first book ever published by Tule Publishing!

This story features members of both Megan’s beloved Grey and Flint brothers families, and is as sizzling as a Montana summer!

Five years ago, when Sydney Campbell came through Marietta on her way to the big Grey family Christmas, she ran into newcomer Jackson Flint in Grey’s Saloon. Directly into him.

In Montana to build some bridges with his older, billionaire half-brothers, Jackson didn’t plan to stay. Sydney was just visiting family from her high-stakes life in D.C. For one night they lit each other on fire, kissed goodbye, and never thought they’d see the other again.

But Jackson built more than bridges and put down roots. And just about every holiday, he’s watched Sydney turn up in town. The fire that always blazes between them gets hotter every visit, but this time is different. This fall, Sydney decides to stay a while. With the 85th Copper Mountain Rodeo taking Marietta by storm, Jackson knows this is the chance he’s been waiting for.

And he means to take it—if he can convince the only woman he’s ever wanted that there’s more freedom in loving him than letting go.

Note: Tempt Me Please, Cowboy is part of the 85th Copper Mountain Rodeo series published by Tule and written by different authors.

Connected Books

Tempt Me Please, Cowboy

Explore the Greys of Montana Series →

Explore the Montana Millionaires Series →

Start reading

Tempt Me Please, Cowboy

Jump to Buy Links →

Chapter One

He was exactly the kind of trouble she needed.

Six feet and then some of lean muscle packed into jeans, boots, and a white T-shirt that every woman in a ten-mile radius of Grey’s Saloon here in Marietta, Montana, was going to dream about tonight.

Herself included.

And that wasn’t even getting to the dirty-blond hair, a little too long and the kind of messy that led straight to more dreaming, plus a set of amused green eyes that were a health hazard all their own.

Sydney Campbell stopped pretending to do her brand-new job as the worst bartender in the history of the old saloon that had been in her family since a branch of Greys escaped the east. They’d found Paradise Valley and decided that looking for copper in the nearby hills was thirsty work. Better still, that they should address that problem. They’d been doing exactly that ever since.

She paid no attention to her uncle Jason’s irritated muttering about firing her even though he’d only just grudgingly hired her in the first place. Because unlike the many people packed into this place tonight who were very careful with the current proprietor and his legendary bad mood of about twenty years and counting, she knew he was all bark.

Well. Mostly.

And anyway, she wasn’t the only person staring.

Because she wasn’t the only person in the saloon with eyes.

“I’m supposed to be doing normal things like normal people,” she reminded her uncle when he scowled at her, and then smiled angelically at him when that scowl deepened.

“I didn’t realize ‘normal’ was on the table,” he growled.

But he left her to it.

This was the main benefit of letting her entire, over-involved extended family think that she was having a nervous breakdown. That her arrival in town heralded an epic collapse of uncertain nature. That she was in the throes of a cataclysmic personal event.

Sydney hadn’t meant to let them all think that. Not really. But she hadn’t corrected them, either.

What else could explain her sudden decision to relocate to tiny little Marietta for an indeterminate amount of time this fall? Sydney usually only came to Montana for Christmas, family weddings, peremptory summons from her perpetually unamused grandmother, and the like. She flew in, smiled like a well-adjusted and potentially well-rounded person for no more than a long weekend, and then flew back to reality on the red-eye.

Because the reality for most of her adult life was that she was busy, and not in the way everyone liked to claim they were so busy so busy so busy these days. Sydney spent night and day in her office at Langley, where she rarely knew or cared if it was night or day because she was lost in all the data that was always scrolling across her many screens and through her head. She was the kind of busy that when her phone buzzed, she always had to answer it, and she was expected to appear in a nearby office within minutes or at the Pentagon within the hour.

She was so busy that when she actually got to go home, she sometimes had to take a minute or five to remember that yes, in fact, she had a small, soulless apartment in nearby McLean, VA, chosen years back so that she was never too far from work. But she was usually at work, so every time she actually went back “home” she felt as if she was staying in a hotel. She’d never bothered to put up pictures or decorate. It had come finished and she left it that way because it was easier. No muss, no fuss.

She had no pets. She saw no people outside of work because she had no time to see anyone. Her friends and family had to content themselves with erratic phone calls and texts at odd hours.

Only other people with all-consuming jobs understood what it was like, and that it wasn’t sad. That she was not depressed or riddled with ulcers or whatever they liked to think, simply because her job was the significant and consuming relationship in her life and had been since she’d been recruited out of Georgetown. Everyone else used words like “workaholic” and “stress case” and so on, never understanding that those were compliments in Sydney’s world.

Some of her friends and family claimed she was a spy. Others preferred to call her a flake.

Sydney was neither, but she neither confirmed nor denied it when people said these things to her face. She could only imagine what they said when she wasn’t around, because she knew her family enjoyed nothing more than diving deep into the psychoanalysis. Preferably over drinks served right here in this saloon.

It wasn’t a stretch for them to imagine it had all become too much for her, because they thought it should have been too much for her years ago.

That wasn’t the truth of things, not precisely, but Sydney had decided to go with it and it had already borne some pretty excellent fruit. Her cousins, usually notable for their benign mockery and sarcastic references to everything under the sun and especially to each other, were forced instead to attempt pleasantries. They’d gotten the news through the lightning-fast Grey family grapevine last night and had called her in a wave earlier today.

Most of them were bad at pleasantries, being genetically predetermined toward intensity.

Or maybe they were just unused to Sydney actually answering her phone.

What she’d realized was that she should have pretended to be fragile years ago. It was hilarious.

But tonight, she wasn’t feeling the least bit fragile.

She tracked his progress through the saloon. Slow and lazy and intent all at once, just like him.

When she’d met him the first time, long ago, she had not been pretending to be fragile. She barely knew that word. That night she’d been after oblivion and she’d managed to get a fairly good grip on it. It was the night before Christmas that year, and she’d squeaked into town last minute on a flight that had skated into Bozeman—and bounced a few times while it was at it—right before they’d started cancelling all flights coming in and out ahead of an expected snowstorm in the mountains.

Sydney had decided that instead of attempting the drive out to Big Sky, where her grandparents lived and hosted Christmas almost every year, she would stay in Marietta and head over very early in the morning with her uncle after he handled the booming Christmas Eve business at Grey’s Saloon. When they could see how bad the storm was going to be, since there was a big gap between newscaster bad and real Montanan bad.

Besides, she had discovered over time that everyone benefited when she put some space between her job and her family, since her family liked to talk about her career like it was her toxic boyfriend.

Some people called it “blowing off steam” and that night, Sydney had gotten into the tequila to see just how steamy she could get. And she’d been having a grand old time. She’d been hanging out with a girl she’d used to play with in summers long past, when her airy, careless mother would park her kids in Montana for most of June, July, and August and take off to follow her bliss—meaning her latest lover—wherever it took her.

Sydney and Emmy Mathis had been summer friends. Close when they saw each other and fine when they didn’t, and Sydney had been delighted to discover that held true once they were grown, too. Emmy now lived in town because she’d married the one and only Griffin Hyatt, another summer-in-Marietta guy who was now a tattoo artist at such a high level that people traveled from all over the world to little Marietta, Montana, for a little ink directly from his hand. He and Emmy had come out with a circle of friends as well as their sharp-eyed grandmothers—who drank more than everyone else—and they’d all been in a festive mood that Christmas Eve.

The Grans, as the grandmothers were known all over Crawford County, had been drinking all of Griffin’s tattooed and bearded friends under the table. Emmy had long since shifted to Cokes. Sydney couldn’t really say how many shots she’d had, which to her mind was the point and purpose of shots. That was the sort of data she didn’t need to hold on to, so she didn’t. It was all part and parcel of the Christmas spirit.

Though she did remember, with perfect clarity, when she’d decided she needed to step outside to see if a burst of frigid air might sober her up a little before her uncle Jason cut her off. Something she had no doubt he would then want to discuss before dawn as they inched through new-fallen snow all the way to Big Sky, no thank you.

That was what she told herself, but it wasn’t really the reason. He would cut her off when he felt like it no matter what state she was in, and his lectures did not require an inciting incident. The real reason was that Sydney wasn’t a sentimental person. She wasn’t forever surfing about on the tides of various emotions like Melody, her impossibly dramatic mother, who Sydney loved dearly and also was very happy to see but rarely.

She wasn’t like her mother. She could never be so careless and emotional. She didn’t like to think about the fact that the air was just… different in Marietta. That even in the crystal clear cold of that December night with a storm sitting heavy in the hills, there was something about standing outside and taking such a deep breath that it was like inhaling the stars.

Sydney didn’t wax poetic. She dealt in facts. She put data and details together, synthesized seemingly unrelated tidbits of information, and drew connections no one else saw.

That was some damn fine poetry right there.

But she didn’t let herself think things like that and she certainly didn’t say things like that, so she’d told the alarmingly clear-eyed Grans that she was getting some air.

Of course you are, dear, Gran Martha Hyatt had said serenely. That will freeze the alcohol right out of your bloodstream, I’m sure.

Perhaps it’s not the alcohol that needs the breathing room, Gran Harriet Mathis had added in a similar tone.

Both with smiles that Sydney had chosen to ignore, because the old women were knowing and strange but they didn’t actually know anything about her. No one did, and not because she was secretive, as her older sister Devyn liked to claim. But because there was nothing to know about her except what was classified, and anyone who needed to know that already did.

She had hurtled for the door to the outside, maybe a little too desperate to get away from those knowing old lady smiles, thrown it open to charge straight out, and had instead slammed into the person coming in.

Directly into him.

So hard that he’d had to take a step back and grip her by the arms to keep them both from toppling over and doing a header on the icy sidewalk, straight into the snow.

But he had risen to the occasion, instantly.

She thought about that now as he did his usual thing, wandering through the saloon, greeting people he knew, and pretending he didn’t know exactly where Sydney was. Or notice that she was looking right at him.

Sometimes she was the one who pretended not to see him, and that was fun too.

But either way, she knew this game. And every time they played it, everything in her turned bright and achingly hot with that same longing that had rushed into her on a cold sidewalk in December, filling her up in place of all those Christmas stars, an intoxicant all its own.

That first night, they had stayed out in the dark together, holding on to each other a whole lot longer than necessary to simply remain upright. Sydney had been laughing, telling herself it was all that tequila, and he’d looked a little bit like he’d been punched straight in the face.

Like he was dazed, somehow, and not from their collision.

He wasn’t fragile either.

And it was true that she’d spent a lot of time in the years since, five years to be exact, thinking about that particular poleaxed expression he’d wore in those first frigid moments. She remembered them as a blinding rush of heat. She didn’t have a lot of nights in that bed of hers in her barely used apartment. She mostly slept, when and if she slept, on the couch in her office or on the floor. And yet every single one of the nights she actually went home involved her lying in that strange bed, pretending to sleep, running through moments like that one.

Almost like she was analyzing them. Looking for connections. Drawing conclusions.

You’re going to catch a chill and freeze to death, he’d said, and it will be my fault for letting you stand out here without a coat.

She’d learned so many things about him in that moment. It was his voice. She heard the Texas in it. The drawl. She already knew that he was strong because she could feel it all around her. He could have lifted her straight up from the ground if he’d wanted and she had the happy little notion that he did want that. She knew that he was taller than her. She knew he was chiseled to perfection, there in jeans and boots that told truths about his form and the heavy coat he’d already unzipped, happily, so she could see there were no lies on the rest of him.

He was all muscle. All man.

There was no getting past the fact that he was wildly, astonishingly hot. She’d told herself then and later that it was the tequila and maybe that had helped, but it had been five years now. There was no getting around the fact that it was him, too.

And that little hint of Texas was like hot sauce on top, making everything smoke.

I’m from generations of good Montana stock, she had replied, smiling wildly for no good reason. I’m not saying I’m going to take a nap in a snowbank, but I’m also not going to freeze to death in three seconds.

I’m from Texas, darlin’, he’d said, in case she hadn’t worked that out. And I might.

He hadn’t let go and she hadn’t pushed the issue, because she really didn’t want him to let go. She liked that he’d called her darlin’ like that, like she was the kind of woman men used endearments on when she knew she wasn’t. She never had been. Sydney was spiky, combative, blunt. Everyone told her so at work, and those were compliments.

But he’d drawled out darlin’ like he meant it. And she’d watched, outside in the hushed dark of Marietta on a Christmas Eve with a storm coming in, the way the corner of his mouth had curled.

Just a little bit.

As if it was hers alone.

Looking back, she liked to think it was the tequila talking when she’d grinned up at him, opened up her mouth, and said, But if you’re worried, we could always warm each other up.

Like she was the kind of darlin’ who flirted with men that way.

Or at all.

But that night, she had been. And her reward was that she’d watched his dark green gaze go smoky like his voice.

Glad I was here to keep you out of that snowbank, he’d drawled. I’m Jackson Flint.

And he’d been warming her up ever since.

Jackson had been a newcomer in Marietta back then, the previously unknown half-brother to the Flint brothers—who were famous billionaires out of Texas, according to all the gossip Sydney had ever heard about them. Jonah Flint still did his Texas thing, though he also spent a lot of his time over near Flathead Lake, where he had a whole lot of land and the sort of ranch men like him used for extended business retreats. Because men like him had time for extended business trips, their currency being money and power. Not information and the element of surprise, the currency Sydney knew best.

It was Jonah’s twin Jasper Flint that folks in Marietta knew best, because he’d come in and bought the old train depot out from under the nose of the many history buffs in sprawling Crawford County. He’d also helped—Sydney’s family muttered that really, he’d entirely funded—the turning of the old Crawford mansion up on a hill above town into a museum that commemorated the sometimes shady doings of old Black Bart. Black Bart had been the Crawford ancestor who settled in the town right about the time the Greys started slinging drinks, but he’d gone more railroad baron than barkeep.

Jasper had opened up FlintWorks Brewery after he’d walked away from Texas, brewing his own beer and ale and winning awards for his trouble. He’d made the place family friendly, with food and music until early evening, when families could head home and anyone looking for trouble could head for the other bars in town that catered to it. Jasper had then gone on to win the town’s heart because he’d married Chelsea Crawford Collier herself, who had been a schoolteacher when he’d met her—if struggling with the weight of her late mama’s expectations regarding the Crawford legacy, according to all sources—and was now the mayor.

Guess she sorted out that legacy, Sydney had said when her aunt Gracie had filled her in on this tidbit.

She lives up in the old mansion now, the part that isn’t a museum, and was elected in a landslide, her uncle Ryan had said with a laugh. It feels like a full Marietta circle.

Not that Jackson had known any of that back then on that frigid Christmas Eve. After years of acquiescing to his mother’s feelings about their shared father, not a good man at all, he’d come to Montana to see if his brothers were worth getting to know.

They’re all right, Jackson had told Sydney, gruffly, when she’d seen him again after that first Christmas.

They hadn’t kept in touch after that wild, explosive night together. They hadn’t even exchanged numbers. It felt like pure chance that Sydney had ended up coming back to Montana that year for one of her cousins’ weddings that so many of them liked to hold here in Marietta for a variety of sentimental reasons that Sydney only pretended to understand.

But she’d walked into Grey’s and there he’d been. And it was only once he’d smiled at her in that slow, hot, bone-melting way of his that she’d accepted that the prospect of seeing him again was the entire reason she’d decided to go into Grey’s in the first place that night.

I’m glad to know that they’re not too bad, she’d said. For billionaires.

She’d let him buy her a drink. She’d let their fingers brush, so the heat of it could gallop through her. And she’d very much enjoyed letting her imagination run wild with all the things he could do next.

And then he did them.

All of them.

The same way he did every time she’d made it back to Montana since. He had turned into a staple of her trips out west. See a little family, enjoy Jackson and all his many talents, and look forward to the next time without ever knowing when that was going to come.

But this time she wasn’t here for a couple of days here, a long holiday weekend there.

This time, she was staying for the season.

What you mean you’re staying in the Graff? her grandmother had demanded when Sydney had called to tell her she was coming to town and staying a while. You can’t stay in a hotel. You are a Grey, Sydney. What will people think?

I don’t know any of the people you mean, Sydney had replied blandly. So I couldn’t speculate as to their thoughts, Grandma.

Elly Grey, never a cozy grandmother at the best of times, had not appreciated that remark.

But Sydney had no intention of giving up a hotel room in the gorgeous old Graff, renovated by local hero Troy Sheenan a decade back to make the most of its Old West splendor, especially when there was the very real possibility of ghosts. Besides, the rooms in the old hotel were pretty and bursting with character, unlike her sad apartment back east.

And anyway, the family options available to her were not appealing. She could stay out in Big Sky with her prickly grandparents, no thank you. She could bunk down in one of Uncle Jason’s back rooms at the bar or one of her cousins’ old rooms in his house of bitterness, another hard pass. She could immerse herself in the chaos of her cousin Luce’s life now that she was divorced and forever at war with her ex, complete with her teenage sons stampeding about, but that sounded possibly the worst of all.

Her cousin Christina was over in the Bitterroot Valley and she’d wondered if she should head that way for a little change of pace, but Christina and her husband Dare were neck deep in the small kid thing and Sydney knew herself far too well to imagine that she could suddenly bloom into a nanny sort of person. Even indirectly. Her aunt Gracie and Uncle Ryan had offered their guest room, but Sydney had told them she didn’t want to put them out by being there on the rare occasions they weren’t off leading their outdoor and adventure trips that ran all year.

This was all perfectly true. But she understood, now that she had Jackson in her sights again, that her decision had really had very little to do with putting out her family members.

It was that she didn’t want to have a discussion with any of them about where she might be at night. Or who she was with.

Because she fully expected it would be with him.

Jackson Flint, who was, she could admit it, the main reason she hadn’t thought too hard about it when her boss had suggested she take a few months off to run through the vacation days she’d been accruing for years. And to get her head on straight, in his words.

Sydney knew perfectly well her head didn’t need straightening. Her head was on just fine. Her boss knew it too, but had to suggest otherwise. And because they dealt in innuendo and making connections between possibilities, there was no need to spell things out.

Sometimes things happened that everybody needed space from. And sometimes, when her work embarrassed the wrong people, it was the kind of space that necessitated that she not show her face where said people might see it.

She might have been a little more worked up about the injustice of that, but the minute her boss had started talking about taking the season—coincidentally, the exact amount of time it would take before the particular official who didn’t want his failures looking back at him with Sydney’s face to move on to his next post—she’d started thinking of a whole fall in Montana.

And not just Marietta, this place her family had helped found and where Greys had lived ever since, as ubiquitous as Copper Mountain that stood sentry over the town and the stretch of mountains that cluttered up the horizons. She loved her family as much as she was capable of loving anything, but really, it had been Jackson who flashed in her mind.

He was why she’d figured she could handle a season away from the job.

She’d spent her first night out in Big Sky explaining to her grandmother why she wasn’t staying there until New Year’s, which had gone even worse in person. Today she’d fielded phone calls from her sister and all the Grey cousins while checking herself into the Graff and then convincing Uncle Jason to give her a job.

Because she needed something to do. She wasn’t a sit around and relax kind of person.

And then she’d waited.

Because she and Jackson never called each other, though they had broken the no-phone-numbers barrier some years back. What usually happened was that they saw each other, then they set each other on fire.

Again and again and again, until she had to go.

It was the perfect system, in Sydney’s mind.

So she settled in and watched as Jackson did his thing. He was like a slow-moving comet streaking his way through the crowd of people, that much brighter and that much hotter than everything and anything around him. She could hardly keep her eyes off him, but then again, she wasn’t trying that hard.

She found herself smiling as he took his sweet time making his way over to the bar.

But when he did, it was like everything else fell away except the two of them.

“They’ll hire anyone around here,” Jackson drawled, his green gaze already hot and deliciously dark.

“It’s a shocking example of nepotism,” Sydney replied, nodding her head in agreement. “I’m personally appalled.”

She pulled him out a bottle of beer, not the kind his family brewed over at FlintWorks, where he’d been running things for a few years now. She even opened it before she slid it across the bar to him.

“Mighty obliged, darlin’.” He was all drawl.

“I live to serve, cowboy.”

His eyes gleamed. “Do you now.”

And for moment they stood there, in the heat of it.

Jackson took a swig of his beer and set it back down on the polished wood surface. Sydney leaned forward, sure that he was about to offer one of his invitations. They were always hot. And he always delivered.

She found herself forced to admit that if he hadn’t come in tonight, she would have had to break protocol entirely and go looking for him.

Looking at him now, she wasn’t sure why she hadn’t started that way.

There weren’t a whole lot of things she wouldn’t do to hear this man call her darlin’ in that way he did.

She was already thinking of all things she could do in return. All the things she would do. Her hands on his body. Her mouth moving like fire over his skin.

Every time she saw him, she couldn’t believe that she’d made it so long between hits.

Sydney remembered where she was, barely, and made sure that her uncle was down at the other end of the bar, out of earshot.

“I have a room at the Graff,” she said.

She watched Jackson take that information on board. Because by now, he knew things about her. Like that she always stayed with family when she was in town.

He took his time tasting his beer. “You always say that your apartment in DC feels like a hotel room.” And that was disconcerting. She didn’t remember telling him that. Then again, she supposed there was more talking on the nights she’d spent with him than she cared to remember. Because there were so many more interesting things to focus on. “You trying to see if there’s some difference between the two?”

“The Graff is a much nicer hotel. My apartment can only dream of such splendor.”

He looked at her, his green eyes steady, bright, expectant. Almost as if he thought she was going to say something.

And suddenly, for no reason she cared to examine, Sydney felt nervous. That was the only possible explanation for the sudden dizzy feeling in her belly, like a swarm of butterflies.

The analytical part of her, that in every other place but this one was the only part of her, kicked in. Hard. What did she actually know about Jackson Flint? Her personal policy was not to dig into people she knew in real life, because that was creepy, and she’d held to that. For all she knew he had a wife. Four kids. Whole other lives.

Something deep in her gut told her that was impossible, but wasn’t that exactly what the other woman in all those scenarios wanted to think?

Then again, Sydney didn’t actually need to run a background check on Jackson Flint. That’s what a close-knit town like Marietta was for. If he was a bad one, someone would have mentioned it in Sydney’s hearing. She’d never asked and no one had ever confronted her, but she was fairly certain more than one member of her family had seen her talking to him in the saloon before.

Still, she was forced to acknowledge the unfortunate reality that she had no idea how Jackson was going to take the news she was about to impart.

Maybe he liked her only enough for a couple of nights a year. Maybe he didn’t want any more than that. He’d never indicated that he did. She’d always found that evidence of his superiority over all other men. She’d loved that it was part and parcel of their hands-off approach, because it made their hands-on times that much more exciting.

But this was different. She hadn’t really let herself think about what his reaction to that difference might be.

Or how she would respond to it if it was… not great.

“I’m going to stay a while,” she made herself say, because she was blunt and abrasive and prickly, and she thought those were positive things. She said things that other people didn’t say. She was paid for that. She was good at that.

She was so good at that she’d been sent on paid leave.

Suddenly it seemed, in that moment, critically important that she remember the things that she was good at.

Jackson had no reaction to what she said, which seemed like a reaction all its own. He stared back at her for so long that she began to wonder if she hadn’t spoken at all. If she’d only intended to and the words were still sitting there on her tongue.

He looked away for a moment, then down at his beer. He fiddled with it as if he was going to pick it up and take another pull, but he didn’t.

“Define ‘a while,’” he suggested.

“You know,” she said in a breezy sort of way that wasn’t her at all. “A season.”

“An actual season? Meaning three months? The fall equinox right on to the winter solstice? That season? Because it hasn’t actually started yet. It’s still technically summer.”

“That’s maybe overly precise.” She thought about how she’d been sitting in her boss’s office, the sun she rarely felt on her actual skin beaming in, thinking of Jackson. But she had been thinking of him naked. She had been thinking of him after this conversation. She had not thought about having to live through this conversation at all. “Until New Year’s, I expect.”

“New Year’s,” he repeated. “It’s going to be Labor Day on Monday, Sydney.”

“I had no idea you were so interested in the calendar.” And maybe that was a little too much edge in her voice, but this was the strangest conversation she’d ever had with him. And did not appear to have anything to do with climbing him like a tree, her favorite and really only leisure activity. “Or equinoxes, solstices, and public holidays, for that matter.”

“I’m interested in all kinds of things.”

Jackson’s voice went lower, and that was better, but also worse. There was a different heat, then.

He was studying her in a way that made her feel prickly all over, and only partially because she didn’t like being the subject of that kind of investigation. She was the one who collected data points. She didn’t care for the notion that he was the one doing the collecting. Or that she was providing any usable data to him in the first place.

“So if I’m following this, you woke up one morning and thought what the hell, then threw in your fancy DC life of secrets to be a barmaid?”

“A bartender, thank you. Even barkeep would do, for that archaic flair. I think you know as well as I do that my uncle Jason isn’t about to let anyone treat me or anyone else behind this bar like a barmaid.”

“But that’s what you’re going to do for the season. You will live in a tiny town in Montana, serve folks drinks, and wait for the new year.”

“Some people would call that a life of ease and relaxation.”

“Would you?”

She wanted him to call her darlin’ again. It was beginning to feel actively oppressive that instead he was… quizzing her on something she had no intention of talking about. Sydney hadn’t realized that it would require this much talking anyway.

“My family is under the impression that I’m having a nervous breakdown.” She smirked a little, hoping that was a little softer than all the edges poking around inside her now. “I may have given them that impression.”

“Are you?”

Direct and to the point. That was the thing about Jackson that drew her in, time and again. There was the drawl and all that magic he could conjure with his hands, his mouth. But when it mattered, he didn’t beat around the bush.

“I don’t believe so,” she said, because she could admire the directness even while wondering why they were standing here having a casual conversation when they could be talking about when and how they could tear each other’s clothes off. Or better yet, doing it. “I’m thinking of developing a drinking problem, though. It’s expected. It would seem odd if I didn’t, don’t you think?”

Once again, it was like he was seeing inside her skin. As if there were hieroglyphics there that only he could read, and she should have found that alarming. Instead, it made her glow, inside and out, with a particular wild heat that settled heavy between her legs.

His smile was made of fire and glory, and it was the best thing she’d seen in months. She felt it go through her like a new heat all its own.

“Darlin’,” he said—at last—and she felt that shiver all over her like the first caress of the night, “I have a much better idea. Get drunk on me.”

And for the first time since she’d got on that plane at Washington Dulles, aware that she was facing down an unprecedented four months of workless freedom—a nightmare by any reckoning—Sydney thought to herself that this Montana might just work out after all.

End of excerpt

Rebel Heart Books is my absolute favorite bookshop. I'd love it if you'd support this woman-owned, delightful place where you can also get signed copies. See if this book is available through them. Thanks!

Tempt Me Please, Cowboy

is available in the following formats: