~ Hazel Beck is the pen name for two authors (Megan and Nicole Helm) writing together ~

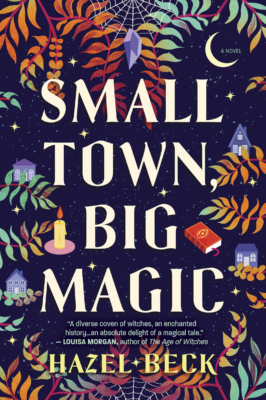

Small Town, Big Magic

Book 1 in the Witchlore Series

HEAT

LEVEL:

Fun & Flirty

There’s no such thing as witches…right?

Emerson Wilde has built the life of her dreams. Youngest Chamber of Commerce president in St. Cyprian history, successful indie bookstore owner, and lucky enough to have her best friends as found family? Done.

But when Emerson is attacked by creatures that shouldn’t be real, and kills them with what can only be called magic, Emerson finds that the past decade of her life has been…a lie. St. Cyprian isn’t your average Midwestern river town—it’s a haven for witches. When Emerson failed a power test years ago, she was stripped of her magical memories. Turns out, Emerson’s friends are all witches.

And so is she.

That’s not all, though: evil is lurking in the charming streets of St. Cyprian. Emerson will need to learn to control what’s inside of her, remember her magic, and deal with old, complicated feelings for her childhood friend–cranky-yet-gorgeous local farmer Jacob North—to defeat an enemy that hides in the rivers and shadows of everything she loves.

Even before she had magic, Emerson would have done anything for St. Cyprian, but now she’ll have to risk not just her livelihood…but her life.

Hazel Beck is the pen name for two authors (Megan and Nicole Helm) writing together. Find out more.

Start reading

Small Town, Big Magic

Jump to Buy Links →

Listen to the Audio Excerpt →

If you google my name—something I only do every other Tuesday because ego surfing is an indulgence and I keep my indulgences on a strict schedule—the first twenty hits are about the hanging of Sarah Emerson Wilde in 1692 in Salem, Massachusetts.

Guess why.

Only after all those witch hits—three pages in—will you get to me, Emerson Wilde. Not a tragically executed woman accused of witchcraft by overwrought zealots, but a bookstore owner and chamber of commerce president. The youngest chamber of commerce president in the history of St. Cyprian, Missouri, not that I like to brag.

Men are applauded for embellishing the truth while women are seen as very confident for telling the truth—and very confident is never a compliment.

If you slog past all the Crucible references and sad YouTube videos from disaffected teens with too much eye makeup, you might read about how my committed rejuvenation efforts have brought ten new businesses to St. Cyprian in the past five years. You might read about our Christmas around the World Festival which, thanks to my hard work and total commitment, brings people from—you guessed it—all around the world. You could read any number of articles about what I’ve done to help St. Cyprian, because it’s not a good day unless I’ve done something to support the town I love best.

And I pride myself on making every day a good day.

Even if most people read about Sarah and the witch trials and stop there, I know the truth about her. I learned all about my notorious ancestor while researching a presentation for my fourth-grade class.

My peers might have preferred Skip Simon’s bold and unlikely claims that he was a direct descendent of the outlaw Jesse James, but learning about Sarah changed my life. The reality of Sarah Emerson Wilde is that she was a fierce feminist who wanted to play by her own rules. A nonconformist who wasn’t interested in playing the perfect Puritan, and therefore a direct threat to the Powers That Be. Following her own rules, ignoring theirs, and trumpeting her independence got her killed.

Sarah wasn’t only a tragic figure. She was also a fierce martyr who would have hated being called either.

In retrospect, it was maybe too much for Miss Timpkin’s fourth-grade class.

But ever since then I’ve considered Sarah my guiding light. I’m proud to have such an exceptional, indomitable woman in my family tree. My great-grandmother times nine, to be precise. I’ve always felt that I owe it to myself, the Wilde name, and Sarah to be a strong, independent woman who doesn’t let the patriarchy or anything else get her down for long.

“And I don’t,” I announce brightly to the quiet of the early-morning kitchen of my family’s historic house.

It’s a Tuesday in March and I have plans. I always have plans. It’s what I do, but these are particularly epic, even for me. I might have been born too late to speak feminist truth to Puritan patriarchal power, but I have my own calling.

I am here to make St. Cyprian a better place.

Don’t laugh.

You can’t fix the world until you sort out your own backyard. I intend to do both.

Since my first St. Cyprian community project with my second-grade class, I have put everything I am into this shining jewel of a river town, the people lucky enough to live here, and the shops that carve out their spots on the cobbled streets—like my own intensely independent bookstore.

For all the women who came before me who weren’t allowed. Or those who carved out their way and were shunned for it.

Fist pumps optional.

I pump a few on my own in the kitchen, because there are few things in this life that psyche a girl up more than a fist pump. One of those things is coffee. Another is sugar. Combine all three and I’m ready to face the day.

But first I need to face my roommate.

My roomie and best friend, Georgie Pendell, grew up in the rickety old house next door, but moved in with me when she could no longer bear another moment of agony in her parents’ house—her dramatic words, not mine. She’s been here five years, sprawled out over the third floor and using the extra bedroom I’d assumed she’d make into an office as a library instead.

Mind you, what Georgie calls a library gives me hives. It’s an overflowing catastrophe of books piled into tottery towers that she refuses to let me organize for her. The last time I tried to go inside, the door only opened about two inches before hitting one of her stacks.

She insists it’s exactly the way she wants it.

And that’s fine, because Wilde House is big enough for the both of us. In fact, bigger than we need. With my parents gone living the high life in Europe and my sister’s defection to who knows where after our high school graduation, the house had seemed too big. I had been thrown for a loop when both my sister and parents left St. Cyprian within a year of each other—though I’d rallied the way I always do. My sister, Rebekah, had always been a free spirit. My parents had always been socially ambitious—so why not take that as far as it could go on the Continent? I had the town. I had my friends. I got to live in this piece of history with my grandmother. Yet when my grandmother died a few years later and left me here alone, the old house felt like an ominous, rattling thing that might swallow me whole. Winter had seemed to seep in, cruel and unforgiving. The halls had seemed too long, the lights too dim.

Possibly I was grieving. The loss of Grandma. The loss of my family, who I knew had their reasons for staying away, in Rebekah’s case because she always had reasons no matter how little she communicated those reasons. Or returning only for the funeral, in my parents’ case, and then rushing back to their European adventure.

It felt a little stormy there for a while.

My silly, happy, eccentric best friend moving in has been like letting in the sunshine.

Organizational challenges aside, having her here makes these early mornings with the whole of Wilde House creaking around me, like it’s singing its own song while I wake, feel less…lonely.

Not that I allow loneliness in my life. I swat it down like an obnoxious fly anytime it pops up. Because loneliness is a betrayal of all the women who came before me and I am not going to be the Wilde who lets them down. I’m the current caretaker of this landmark of a house that’s been in my family some three hundred years, since the first Wilde wisely made the long trek away from the Massachusetts Colony and settled down in this part of Missouri where two great rivers meet, the Mississippi and the Missouri. I like the idea of roots that deep and rivers that tangle together. I like this house that towers above me with its uneven floors and oddly shaped rooms. I like where it sits in town, on one end of Main Street like a punctuation mark.

And I really like that my best friend is always right here, within reach.

Because before I head off to my beloved Confluence Books today, I need to get Georgie on board for an Official Friend Meeting tonight. Being a young, ambitious, independent woman in charge of the chamber of commerce in the most charming river town in Missouri—and therefore America—comes with its challenges. A strong leader knows when to lean in to her community, and I do. My friends are always the first people I turn to when I need some help.

I tell myself that I would do that even if my family was still here. That my friends are my family. My parents and sister are the black sheep—not me. Their leaving, their lack of contact entirely or bright, shallow, early-morning messages from abroad is their choice.

And their loss.

My friends stayed. They love St. Cyprian and loved my grandmother too. They are mine, and I am theirs. Just like this town I love so much.

Still, sometimes I like to make a gathering official because that makes it more likely we’ll get to the constructive advice more quickly.

I head for the curving narrow stairs that will take me up into the house’s turret. It’s never been my favorite part of the house—it makes me think of princesses and fairy tales and other embarrassingly romantic things that have no place in a practical, independent life—but it suits Georgie to the bone. Like it was made for her.

I eye the newel post as I start up the stairs because it’s shaped like a grinning dragon and I’ve never understood it. The Wildes are the least fanciful people alive. Pragmatism and quiet determination would be our coat of arms if we had such a thing, but we’re Midwesterners, thank you. Coats of arms are far too showy.

The dragon grins at me like it knows things I don’t.

“That is unlikely,” I tell it, then close my eyes, despairing of myself.

There is no room in my life for the kind of whimsy that results in discussions with inanimate objects. Especially a dragon. A sometimes creepy dragon who hunches at the foot of the banister like he’s guarding the house.

“Stop it,” I mutter at myself—and possibly at him—as I head upstairs.

Once on the third floor, I eye Georgie’s library door as I pass it, itching to get in there and establish some order, but sometimes friendship comes before logic. Or intelligible shelving systems. At the end of the hall, her bedroom door is ajar, and I can see Georgie herself sitting on the wood-planked floor facing the two huge turret windows that take up most of the outside wall. They are flung wide open to the cool spring air and she has her face lifted to the sunrise.

Her curly red hair swirls around her, and she’s wearing enough bracelets on her wrist to perform a symphony of tinkling metal sounds. Like the half hippie, half free spirit she claims to be.

Georgie’s family also has roots in Puritan Massachusetts witch trials but unlike me, she loves getting lost in all that witchcraft nonsense. She pretends she has various supernatural powers to annoy me, but mostly she likes the trappings. What she solemnly calls crystal lore and sage burning. She likes to talk to her cat as if he can understand her and claims his meows are detailed replies that she, naturally, can comprehend perfectly. And she steadfastly claims to believe that Ellowyn, one of our other closest friends, can brew teas that cure colds, repair broken hearts, and curse weak-willed men.

There’s something comforting about how Georgie wholeheartedly embraces the silliness, like this daily ritual of hers. The morning light streams in, making the colorful crystals she’s arranged around her in a circle glow.

As I stand in the doorway, she gets to her feet and begins to collect her debris. Her crystals are the only item she owns that I have ever seen her keep in some kind of order. I used to try to help her pick up the various rocks, but she would tell me things like I put the malachite with the quartz and everyone knows that’s wrong, or that reds and blues shouldn’t touch on Wednesdays, obviously. I finally gave up.

I’ll admit that sometimes I have to shove my hands in my pockets to keep from helping again anyway.

“What brings you to my lair this early in the morning?” she asks without looking at me. I know this is to give the impression that she divined my presence when it’s more likely she heard the creaky board out in the hallway.

She does something dramatic with her fingers in the air, and at the same time a breeze shifts through the wind chimes she has hanging in her windows. A funny little coincidence.

I ignore it. “You’re free tonight, right?”

“Sadly no. In a shocking twist that will surprise everyone who’s ever met me or seen me attempt to dance, I’m running away to Spain, where I will dedicate myself to the study of flamenco. And possibly also tapas and wine.”

In other words, yes, she’s free.

“I need to call a meeting.”

Georgie sighs and looks over her shoulder at me. “Not every get-together needs to be a meeting with a cause.”

I smile winsomely at her. “But some do.”

“Is this about those flyers I helped you put up yesterday?”

I smile even more broadly. If there was an award for best flyer, that one would win it. But then, I’m excellent at flyers. “That flyer was about the new and improved Redbud Festival, Georgie.”

“Yes, I know. I also know that anytime you try to new and improve something in this town, the plague that is Skip Simon descends on you like the locust he is.”

“He hasn’t. Yet.”

“But he will.”

He will. He always does.

I sigh. “Yes, he will. He can’t resist. But I don’t want to fight him.” This time is implied. “I want to find a way to get through to him. Preferably without embarrassing him in front of the whole town.”

Because the only thing I’ve ever been able to do when it came to Skip Simon, from another old and well-to-do local family here in St. Cyprian like mine, was embarrass him.

Publicly.

His unearned victory against me in fourth grade notwithstanding.

There was the kickball game. You’d think a grown man wouldn’t still be mad that a girl had accidentally smashed his face with a kickball in gym class, both breaking his nose and making him the laughingstock of the fifth grade, but Skip had brought it up at least twice in the past six months alone.

There was the olive branch incident. Except it wasn’t an olive branch. It was an extra helping of the fish sticks from the cafeteria that everyone knew he loved. I’d thought he’d find those fish sticks within the hour and maybe we could bury the hatchet. Instead, he’d come back from a week’s vacation—that he claimed was the flu, but he had a tan from lying on the beach in Mexico—to find everyone calling him Stinky Simon. And hadn’t believed I’d been out that same week because I really did come down with the flu before I could take the fish sticks offering back out of his locker.

There was the unfortunate field trip to Mark Twain’s Boyhood Home in Hannibal. The riverboat incident a year later. The ninth-grade intercom thing that even my own friends didn’t entirely believe was an accident, but how was I supposed to know that it could be so easily turned on? Or that Skip and his freshman year girlfriend would choose to use that room to make out in?

Classmates made unfortunate slurping sounds at him for years.

Then there’d been prom. Our parents had urged us to go together despite the many years of discord. They thought our two old St. Cyprian families should be friendlier, and obviously my rebellious sister wasn’t the one to approach for cordiality of any kind. And when they’d had a few drinks, our parents tended to wax rhapsodic about how they’d always had hopes for Skip and me.

Neither Skip nor I shared these hopes.

But we’d agreed all the same, because St. Cyprian is a small town. And because it made sense to make an effort. Okay, that was me, but he was briefly less jerky about things. We even called our awkward plans peace talks.

Then I stood him up.

It was an accident, but no one believed that.

My position, then and now, is that when your always-problematic sister “loses” your favorite science teacher’s chinchilla, you can hardly be concerned about a dance. You initiate search and rescue, in a prom dress, because it’s the poor, lost chinchilla that matters. And given that I was the one who found Mr. Churchilla, you’d think Skip would have forgiven me.

But he didn’t. Especially when the rumor went around that I’d always plotted to stand him up. As if I would descend to playing teen rom-com movie games with Skip. Plus, there was another rumor that Skip himself had actually been planning to embarrass me with something far more cringeworthy than his choice of white tuxedo.

I wish I could say we’d left such silly adolescent issues behind, but on the day of Skip’s coronation—I mean, election, if you could call it that when his grand and formidable mother basically forced everyone she knows into voting for her precious spoiled baby—as mayor of St. Cyprian, I led a town cleanup service project. I had no idea the cleaning substance we’d used in the community center would make the floor abnormally slippery. I was wearing shoes with decent treads.

But Skip was not. He tripped, fell flat on his face and, yes, broke his nose again.

Yes, he blamed me.

The harder I tried to be nice to Skip, the worse I seemed to embarrass him. Over time, he moved on from any actual incidents to simply blaming me by rote. If there is any bad word breathed about him on the cobbled streets of St. Cyprian, he assumes it’s my fault.

But he’s the mayor. What mayor is universally adored? Welcome to politics.

An argument he does not find compelling, sadly. I’ve tried.

Skip might not believe this, but while he can certainly schmooze with the best of them, he isn’t liked by all and sundry. He is mayor here because his family is powerful and because he vowed to keep the town as it is. The sad truth is, no matter how many progressive folks live here, a great many people in the greater St. Cyprian area are afraid of change.

That doesn’t mean they like Skip personally. Yet somehow the blame for any negativity aimed at him or his office or his campaign gets put on my shoulders. When he decides I’m wrong, which is pretty much anytime I get out there and try to change things for the better, he really goes after me.

This is why I need my friends to help me brainstorm ways to deal with Skip’s eventual, inevitable response to my new ideas for the Redbud Festival. Because I’m certainly not going to stop trying to improve St. Cyprian and its tourist-attracting, revenue-producing festivals to appease Mayor Stinky Simon.

I’ve said nothing, and Georgie has stood there studying me. Which means her response will be one I do not like.

Sure enough, Georgie nods as if she’s seen something. She goes to her bag of crystals and takes one out. Then she places the shiny black stone in my palm. “Keep this with you.”

“You know I don’t believe in this stuff,” I say, somewhat desperately. We’re usually good at letting each other be who we are. She lets me march around being bossy and anal. I let her waft around being fanciful and disorganized.

I feel like surrendering to crystals is blurring these lines.

“I know,” she says gently, her other hand coming over mine. There’s no lecture, just a gentle squeeze. “Humor me today.”

“Fine.” I slip the rock into my pocket. “Tonight?”

“I’ll make the brownies.”

“Perfect.” Because there is nothing more perfect than a plan coming together, unless it also comes together with gooey chocolate goodness.

Now I’ve got to get the rest of our little group on board before I open my bookstore. Because my friends are awesome, by definition, and each one of them brings specific skill sets to this kind of meeting. I need them all.

My cousin, Zander Rivers, is a ferryman like the rest of his part of the family. He always lightens the mood and makes everyone laugh, especially when I’m being intense. He always thinks I’m being intense, by the way.

But Zander is even more key to these town domination meetings thanks to his evenings at St. Cyprian’s townie bar. He always knows what the gossip is. And knowing what people in town think, and what they’re saying, makes it easier for me to do things that really are what’s best for them.

Not in a paternalistic, condescending Skip Simon way. In a collaborative, it-takes-a-village way.

Ellowyn Good, on the other hand, is particularly vicious and vindictive—traits I don’t share, but deeply appreciate. Especially because Georgie is very talented at taking Ellowyn’s usually extreme ideas and softening them. Then making Ellowyn think it was her idea all along. Georgie also always supplies the sweets, which helps, because sugar helps everything.

And Jacob North…

I suddenly feel hot and try to cover it with my smile as I leave Georgie’s room.

I tell myself it’s temper as I march down the hall toward the stairs. Jacob is maddening. I’ve spent years telling myself that every resistance—or community service project, call it what you will—needs a Jacob to point out the flaws in a plan. Every single flaw in every single plan, endlessly. I tell myself, as I often do, that Jacob is not a dour pessimist. He’s cool-headed and rooted in reality. Both necessary counterbalances to Ellowyn’s dark imaginings, Georgie’s airiness, Zander’s comedy routines, and what Jacob likes to call my delusions of grandeur.

“Necessary counterbalances are necessary,” I mutter as I hit the stairs.

I text Zander as I walk down to the first floor. He’ll catch Jacob on the ferry and tell him the evening’s plans, and—bonus—I won’t have to hear Jacob’s initial complaints. I’d text Ellowyn too, but she never checks her phone, so I’ll have to stop by her store on the way to mine.

I grab my jacket in a nod to the still-capricious spring weather and sling my messenger bag over my shoulder, then I step outside and pause the way I always do.

Because I love St. Cyprian and I like to take it in.

From my front door I can see down the length of Main Street, a redbrick straight shot as if some man was trying to prove he had dominance over the curving, wild Missouri River. Like men do. Buildings made of local limestone and brick, and even the odd wood-paneled cottage, are crowded on either side of the street and almost all of them are on the historic register. Storefronts boast big windows and swinging signs declaring their names and cute logos. This time of year, the sidewalks are cluttered with chalkboard signs and sturdy pots of early-blooming flowers.

I set off with the same song in my heart that’s swelled in me since I was a kid.

St. Cyprian is mine and I am St. Cyprian’s.

I’ve never cared much if people find that odd. And they do, which is why I’ve learned to keep it to myself. Mostly.

The sun is shining bright today and everything looks a little sparkly from the rain last night. I wave at Holly Bishop through the window of her bakery and share a greeting with Gus Howe, out sweeping the sidewalk in front of his antique store.

I’ll never understand why my parents chose Europe or why my sister ran away. This is home. It’s beautiful and better still, ours. I can practically feel the history rise up from the brick-lined streets.

My history. Wilde history. The real family history that has nothing to do with hanging for witchcraft back east, but is instead all about strong, determined women who wanted to make each generation a little better for the next. I have a responsibility to that history. To my grandmother, who created Confluence Books when her grandmother passed a drugstore down to her, who had inherited it in turn from her grandmother—a full-on badass who’d run a gun shop and trading post here when St. Cyprian was the frontier.

I stop at Ellowyn’s tea shop, Tea & No Sympathy. Outside, it’s a serviceable two-story brick building with Ellowyn’s apartment stacked above the shop. It was built in the 1800s, so it’s not one of the older buildings in town. Inside, it looks like a charming little European cottage. White walls and paned windows open with luxurious flowerpots on their sills. Teas line the back wall in big antique jars, making you feel like you’re walking into a country apothecary. Possibly circa 1802.

Ellowyn’s selling point is the idea that her teas can cure things. Any and all things, like they’re magic potions. Silly for people to believe, but a smart business move, because the tourists who flock here love the idea that a novelty tea set from a local shop can cure what ails them. I always appreciate a smart business move.

Though I have learned not to liken Ellowyn’s “curated tea blends” to things like fortune-telling, palm reading, or Tarot cards. It makes her testy.

Ellowyn appears from the back in a black apron with her blond hair tied into a swirling mass on the top of her head. “Since when do you want tea?”

“Good morning to you too.” She only looks at me, expressionless, so I drop my shiny chamber of commerce smile. “Since you ignore your phone, I stopped by to see if you’re free tonight.”

Ellowyn narrows her eyes at me. “For what?”

“Now, Wynnie,” I say in as placating a tone as possible, using the nickname she would kill anyone else for speaking out loud.

“Don’t Wynnie me. I don’t want to be roped into putting up flyers or picking up litter all over town or volunteering for some deadly dull committee.”

Her position has never made any sense to me. “Even though all of those things help you as a business owner in this town?”

“Even though.”

I sigh. Sometimes it seems like I’m the only one who cares about our town, but there’s no point having that fight for the millionth time. I know at the end of the day Ellowyn cares about me. That means she’ll help on this, the way she always helps, even if she has to be dragged in, kicking and screaming.

Not always figuratively.

“I need to figure out how to head Skip off at the pass,” I say. “But in a way that does not end with our illustrious mayor embarrassed in front of a hundred people, again, and hating me even more than he already does.”

Ellowyn continues to fuss around with her tea, in and out of bags. She takes different leaves from a selection of jars and pours hot water over them, so a fragrant cloud of steam rises up between us. I breathe it in and feel my shoulders relax. Slightly.

“But embarrassing Skip is one of the things you do best. And also one of my favorite things about you.” She shoots me a grin.

“Be that as it may, embarrassing Skip only makes my life harder. I need help.”

Ellowyn humphs, but I know she’ll relent. She always does.

“Take this.” She hands me the tea she’s just made in a to-go cup.

She waits for me to ask what it is. I don’t. She’ll tell me it’s been specially brewed to cleanse my aura or support my moon connection or something equally woo-woo and ridiculous. I prefer not to know rather than have to pretend it isn’t all absurd.

“Thanks,” I say with a smile instead. A genuine smile. “Tonight at six?”

“Is Georgie making brownies?”

“You know it.”

“I’ll be there.” But her smile borders on evil. “Though I can’t promise my ideas won’t be about how to embarrass Skip even more than usual. He’s a dick.”

I try to look disapproving, but I can’t. She only speaks the sad truth. Skip is a dick.

On the other hand, as one of Ellowyn’s oldest friends, I feel like it’s my duty not to encourage her I Am the Night thing too much.

Either way, I’m smiling as I walk out of her shop and head down Main Street to mine.

Confluence Books sits in one of the oldest buildings in St. Cyprian. A white brick structure with a green roof and shutters around each of the four windows—the big, arched storefront window on the ground floor and the three smaller windows upstairs. The thick wooden door is a bright, cheery red. There’s a balcony on the second floor, currently a simple wrought iron black, but I always think about painting it a bright color in the spring before things really start to bloom.

This year my focus has been on a new and improved Redbud Festival, so I haven’t had the time. Because I love Confluence Books with my whole heart, but my role in the community sometimes takes precedence over the projects I’d like to do here. As long as I sell books, and I do, the cosmetic details can wait.

I step inside this building that’s been in my family for generations. I turn the book-shaped sign on the door from Closed to Open and gaze around the main floor of the bookstore with satisfaction. My grandmother would be proud.

And despite the inevitable showdown with Skip, I feel good.

Because I love that my friends will help me come up with scenarios to handle our obnoxious mayor, but I have a secret weapon.

I’m Emerson Wilde, last in a line of powerful women, and I can accomplish anything.

End of excerpt

Audio Excerpt

Small Town, Big Magic

Rebel Heart Books is my absolute favorite bookshop. I'd love it if you'd support this woman-owned, delightful place where you can also get signed copies. See if this book is available through them. Thanks!

Small Town, Big Magic

is available in the following formats:

Book 1

Book 1 Book 2

Book 2 Book 3

Book 3